THE RIGHT TO SOCIAL HOUSING AND PUBLIC SPACE

“The right to social housing and public space” project was implemented by the Kosovo Architecture Foundation (KAF) with the support of the Democratic Society Promotion (DSP) project – financed by Swiss Cooperation Office Kosovo (SCO-K) and managed by Kosovar Civil Society Foundation (KCSF). Its main goal was to advocate for equal rights in social, affordable and decent housing for all the citizens, regardless of their cultural, social and economic differences. The project aim was to increase the level of citizen’s satisfaction with public services, to increase citizens and NGOs participation in local public discussions and to increase their influence in policy making. It targeted cultural and socio-economically marginalized groups, local decision makers, and the general public in municipalities of Prishtina, Gjakova, Gjilan, Ferizaj and Fushë Kosova. Implementation of the project started on 1st of September 2015 and is expected to end on 28th of February 2017.

The main aims of the project were:

The training of interest groups in using contemporary tools and methodologies for activism and influencing decision-making processes. The aim of the project is to involve and activate the general society and civil society organizations in political and public life, with the purpose of achieving good local governance, increasing the quality of services, gender equality and integrating minorities and other marginalized groups in fields related to public space and social housing.

Drafting local manuals for social and affordable housing for the citizens, which are supposed to be considered or applied by the Municipality. The manuals for social housing will be drafted based on official laws and documents, existing field conditions, needs of groups of interest, successful examples in the world and in consultation with local and international experts. Through these manuals it is aimed to create strategies and proper living conditions for the citizens.

Establishing inclusive advisory groups for decision-making in social housing. The aim of these groups, which will also include women, disabled people and marginalized groups, is to provide equal dissemination of social housing units within municipalities in the best possible way, by prioritizing the most needed beneficiaries.

Building mechanisms for accountability to the citizens. It includes building a communication/reporting platform for smart phones for reporting the damages or misuse of public space and social housing. Reporting will be done by sending photographs and describing the damage/misuse and its location in the application. These complaints will be sent to the municipality’s inspectorate, which is expected to intervene with the needed measures. Thus the communication and transparency between the municipality and citizens will increase.

Raising public awareness for the universal right to public space and social and affordable housing. Within the project will be organized public debates and discussions among local decision makers, NGO-s and the general public, presentations for high school students and workshops for local students and groups of interest, and will be published informing brochures for the citizens’ rights and responsibilities in public space and for application methods and conditions for social and affordable housing.

Why Public Space and Social Housing?

One of the elements that define a livable city is its public spaces. In recent decades a negative trend of privatization of public spaces gripped all global cities without difference of their typology or status. This trend is even more concerning in developing countries such as Kosovo, where the privatization of public spaces and the neglect to address these issues by the decision makers is very obvious and unchallenged. KAF chose 5 different cities in typology and issues to tackle these problems. The universal right to public space is our main incentive for this project, the public space should be one where any individual regarding his socio-economic, cultural or ethnic background should feel equal. This universal right, more than to any other group, should serve people with disabilities. We all know that our sidewalks, buildings and public spaces are far away from minimal dignifying conditions of access for people with disabilities. For a country that aims to become part of the European Union, inclusive access to public space should be of the highest priority for local decision makers, in particular for the planning and infrastructure departments.

The same applies to Social Housing. Post war Kosovo saw a trend in social division, which was manifested in the worst way in the construction of gated communities in our suburbs, a place where better off financial families could live apart from the other socio-economic groups.

Kosovo, even though it never had a sustainable social housing scheme, it never had socio-economic, cultural or ethnically segregated neighborhoods. Today as a result of many factors, the above mentioned divisions are more than evident and the existing social housing, apart from the controversial living conditions, in almost all cases promote the social segregation of the beneficiaries of the scheme.

Offering safe, decent and affordable housing to all is one of the goals that was adopted in September of this year by the world leaders under the leadership of the United Nations and their program “The Global Goals for Sustainable Developments”. Our project’s guideline on Housing is just this, offering decent housing for all regardless of their social, economic, cultural or ethnic background. For Kosovo the time for addressing this issue is more than crucial in showing that we as a society are considerate and are willing to work on offering shelter for all those that are less fortunate to own or rent. With this project KAF aims to help the local governments in providing best solutions in inclusive social housing and in democratizing and making the decision making process as transparent as possible.

The Right to Social Housing and Public Space project was the first project of its kind in Kosovo. With more than 80 engaged individuals, more than 1000 reports, a conference, surveys, debate and workshops, the project proved to be a success, in particular at informing the general public on the basic rights to social housing as well as public space for all. The publication tried to summarize just some of the findings and work done throughout the project implementation in the five municipalities. The publication also features papers and best case studies on social housing and inclusive public space.

Public Spaces

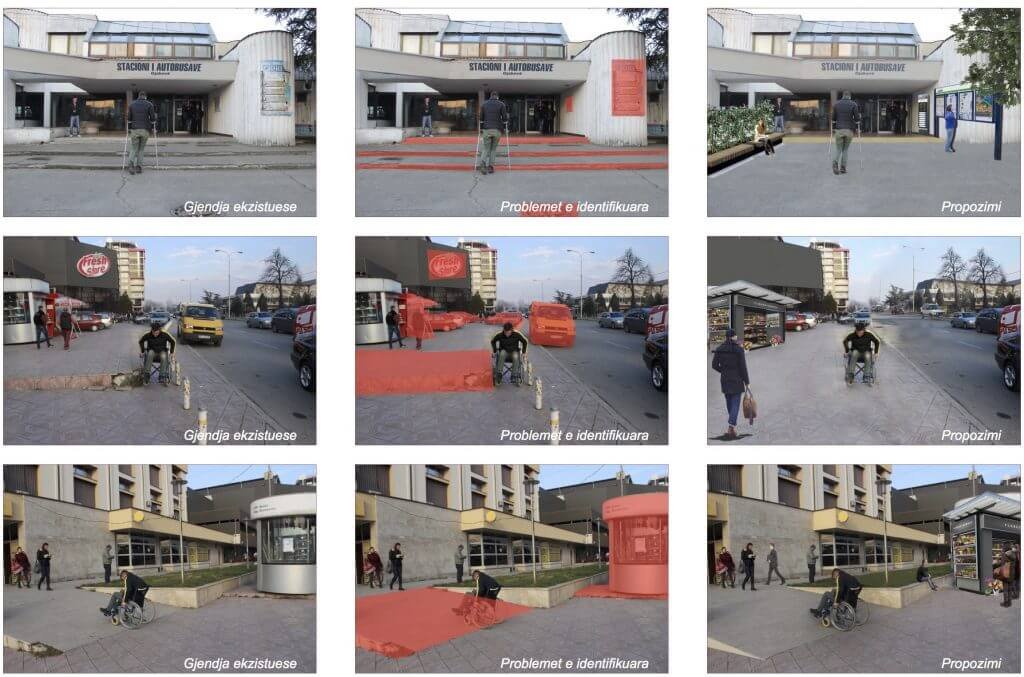

Although public space problems identified in the 5 city project partners were in the biggest part identical, problems such as car occupied sidewalks, no access for people with disabilities, public space privatization, etc. Because of the large volume of produced work by the project team, and its online publishing, for the printed version of the publication we decided to feature only a set of studies.

In Prishtina the proactive group apart from identifying numerous problems in public spaces, social housing and identifying potential spaces for urban regeneration, work that was spread throughout the 18 months of the project, in the last 3 months the group focused on the mapping and visualization of all problems in public spaces from missing sidewalks to illegal landfills. In Gjilan after numerous reports and requests addressed towards the municipality to provide accessibility for people with disability, in particular for the ones in wheelchairs, in the center of the city. The Gjilan proactive group led by its wheelchair user members organized a symbolic initiative where they used hammers to create ramps in the street crossings in the center of the city. This initiative, although very symbolic, drew the interest of a large number of audio-visual and written media. Consequently the initiative and the media pressured the city authorities even further in taking action on this issue, and a couple of months later the city decided to allocate funds from their budget to intervene in the center of the city making the street crossings accessible for all.

In the Ferizaj municipality where with the help of the municipality the Office for Urban Regeneration was created. An important focus was given to identifying the public buildings and their accessibility as well as producing guidelines for the construction of accessible ramps. THe Office for Urban Regeneration and the Ferizaj proactive group was also engaged in the identification of sidewalk barriers for all the streets in the center of the city, and produced a report for the needs of the planning department. For this publication the proactive group chose to focus on the railway crossing, its accessibility as well as on the regeneration of the park situated on the edge of the railway, which although in bad shape is very popular in particular with the elderly. As in the case of Ferizaj, in Gjakova the focus of the work in public spaces was the identification of sidewalk and crossing barriers as well as public buildings accessibility for people with disabilities. The proactive group also used case studies and produced accessibility guidelines for the municipality. For this publication the Gjakova proactive group chose to focus on the mapping of sidewalk and crossing barriers between the main points used by people on wheelchairs and the blind.

In Fushe Kosova where the second Office for Urban Regeneration was created the mapping and analysis work on accessibility in public space witnessed posiitive change after the numerous visits to the 28 and 29 neighborhoods in the outskirts of the city, which are mainly populated with Roma and Ashkali minority. During the first part of the project almost the whole of the work was focused on analyzing these two neighborhoods. The proactive group identified the missing roads, pavements, public lighting, all other basic communal services as well as total lack of green and recreational spaces within the neighborhoods. During the Architecture Week, the project team in collaboration with Bence Komlosi from Architecture for Refugees organized a one week workshop which aimed to engage the local youth in identifying the potential spaces that could be consequently turned into recreational and leisure spaces for the neighborhood. The workshop also aimed to give more responsibility to the youth of the neighborhood in creating public spaces that would provide a better wellbeing for its citizens, new spaces that could be used by the elderly as well as those for recreation by the young. During the second part of the project implementation the proactive group was focused on identifying sidewalk barriers as well as safety levels and measures for street crossings in school and kindergarten vicinities, as well as creating temporary/seasonal pedestrian public spaces in the center of the town by limiting car accessibility on the Dardania main street. During the workshop that was tutored by Elena Madison from the New York based Project for Public Space we focused on two neighborhoods, one was the Dodona neighborhood in Prishtina and the other was the main street Dardania in Fushe Kosova. The surveyed citizens, the project team and the city officials came to an agreement to collaborate in the near future to create a spatial and event program for the street as well as traffic flow for the Dardania neighborhood streets.

Social Housing in Kosovo

Although public housing schemes, both affordable and social, in ex-Yugoslavia were introduced largely after WWII, in Kosovo that came much later during the end of the 60’s and throughout the 70’s and 80’s. This “neglect” is mainly due to the fact that the socialist regime discriminated against Kosovo. Nevertheless after the first collective public housing projects were introduced in Kosovo (Prishtina) at the end of the 60’s, a bigger wave of public and affordable housing started being constructed during the 70′ and 80’s. And although preferences were given to Serbian and Montenegrin minorities, a large number of Albanians also benefited from the schemes.

In majority of the cases the housing units constructed at the end of the 60’s and during the 70’s were of a collective midrise typology. During the 80’s the architectural typology shifted to a highrise and hybrid / megastructure typology, with landmark complexes such as the Ulpiana high-rises locally known as the “Soliterat” as well as the Dardania “C” and the hybrid Spine (Kurrizi) complex.

The low price of the units as well as flexible mortgage models allowed for many citizens to buy out their units. Unfortunately there were a significant number of inhabitants that did not manage to close their mortgages by the beginning of 1990 when the Serbian regime started expelling them from those units.

During the 1990’s the vacant units situated in all major cities in Kosovo were populated with predominantly Serbian newcomers from different parts of ex-Yugoslavia, which came to fill public sector jobs created by the massive expulsion of Albanian workers from their jobs. During the 1990’s public housing sector was exclusively produced for the needs of the Serbian newcomers, which were supposed to boost the percentage of their population in Kosovo. Ironically after the end of the Kosovo war when the Serbian population almost entirely abandoned the Kosovo cities, returning to their cities of origin, mainly in southern and central Serbia, as well as in the newly formed rural “Serbian enclaves”. Those units were then occupied by the same people that used to live there till the end of the 1980’s as well as by the population from the rural parts of the country that had their houses destroyed by the Serbian army.

Immediately after the war, the inefficiency of the UN mission governing Kosovo created a vacuum in the supply of housing in the market. And as in many post war countries the population turned to the informal sector. Although this process provided basic shelter for this population, it created severe physical and social infrastructure problems for them as well as for the cities. Due to the larger scale of the informal neighborhoods, which were usually constructed on public land, cities such as Prishtina, 18 years after the war, are trying to upgrade and mitigate the physical and social disparity between the urbanized neighborhoods of the socialist era with those constructed after the war.

After the establishment of the self-governing structures in Kosovo, first moves towards the establishment of legal frameworks on housing were undertaken. One of the first documents that made possible the construction of typical social housing collective units was the Law on Special Housing adopted in 2010. Several Ministries such as the one on Spatial Planning and the Ministry of Return and Repatriation, as well as numerous Municipalities financed the construction of social housing buildings. The models for the construction of these units was very divers, from direct funding from the Ministries to a private public partnership as in the case of one of the first social housing buildings in Prishtina where a local developer acquired prime land in the outskirts of the city for the construction of a gated community, and in return constructed two social housing buildings at a site that completely lacks social infrastructure. This model is one that serves as the best example of how not to create one’s social housing stock.

Important to note is that throughout this period, from 1960’s to our date, the Roma minority was almost nonexistent in the beneficiary lists of social and affordable housing. It is only during the last decade that we have seen some kind of housing reconstruction for the Roma community around Kosovo, and of course in all cases it is segregated.

In 2015 the Ministry of Spatial Planning Housing Department initiated the drafting of the Law on Social Housing. An internal working group based their investigation on regional and European social housing Laws. The Law as such will be a major step forward for the regulation of social housing in our country, but on the other hand because it is not well defined, it is based on regional legislatures and doesn’t really take into consideration the local context, it is in danger of becoming another Law that is never implemented. The working group that drafted the Law should have based their output on an in-depth ground research that would have produced a contextualized Law that would fit Kosovo’s social and affordable housing demand. Further recommendation for the central government will be elaborated in the conclusion and recommendation section.

During the first part of the project implementation we gathered relevant data on social housing in the 5 partnering municipalities as well as conducted a survey with more than 100 beneficiaries. The team’s findings as well as the assessments of the partnering cities were presented at a conference held in July 2016. The representative of the housing department in the Ministry of Spatial Planning presented their work on the new Law, while Doris Andoni from the Albanian National Housing Agency presented the state of social housing in Albania.

It must be said that all five partnering municipalities, and in particular their departments of social welfare, are doing their utmost in providing shelter as well as social assistance to the people in need. All municipalities had a stock of social housing they were leasing as well as a considerable number of cases of subsidized rent.

On the date of the conference the Gjakova municipality had 44 social housing units, had constructed 115 houses for the Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian community, they are subsidizing the rent for 27 families in need, and are providing physical upgrading funds to more than 100 families. One of the problems they identified during their recent assessment of their housing stock is the existence of 60 housing units owned by the municipality that have been occupied illegally since the end of the war. In 2015 the Gjakova municipality had 240 applications for social housing and subsidies. While in 2016 they provided additional rent subsidies for 86 cases, are in the process of constructing 10 new houses that will accommodate 10 families still living in temporary makeshift structures since the war, as well as with the help of the Ministry of Spatial Planning construct a collective building with 24 units to accommodate the applicants for the social housing.

The municipality of Fushe Kosova which is the smallest of the 5 partnering municipalities focused more on providing permanent housing for its inhabitants rather than constructing low rent / affordable housing units. According to their department of social welfare they aim to at one point provide sufficient housing for all in need.

In the last 3 years the municipality in collaboration with international partners has constructed 60 detached houses as well as upgraded 30 privately owned ones. The municipality of Fushe Kosova has in total 58 social housing units with 56 of them being managed by the city and the 2 remaining ones by the Kosovo Privatization Agency. According to the city officials they are providing shelter for all of its inhabitants in need and ones that are enlisted in the application registry for social housing and subsidized rent. The latter is not a realistic reflection of the situation on the ground, through our analyses and surveys we have discovered that a large number of families, almost all from the Roma and Ashkali community, are not aware of their right to apply for rent subsidies or social housing.

The municipality of Gjilan has a total stock of 53 units of social housing in two collective buildings. In the two last years the city has raised funds from private donors to build 35 houses for people in need as is supporting 39 families by subsidizing their rents. During 2015 the city had 27 applications for social housing, 181 for the construction of new homes, 130 for upgrading as well as 122 applications for rent subsidy. Overall the city of Gjilan provides housing to almost 500 families, with around 80 of them with permanent housing solutions and 40 with rent subsidy. The total number of families receiving some form of social assistance in the municipality of Gjilan including housing is 1100.

The Ferizaj municipality has in total 113 units and in 2016 had additional 314 applications for social housing. The good aspect of the social housing in Ferizaj is that the housing units are in close vicinity to social and cultural services. The municipality also subsidizes the rents for all rent subsidy applications as well as plans to further increase its number of social housing units.

The municipalities of Prishtina under the leadership of Arben Vitia, the head of the Social Welfare, have best grasped the need for an integrated approach to social and affordable housing. They are actively working in reversing the work done by the prior Prishtina administration that created a system of segregated social housing. The department has already under its administration 4 collective buildings with more than 100 units and is also planning to collaborate with local developers in constructing mixed housing developments that would accommodate the high demand for social and affordable housing, as well as provide rent subsidy for a considerable number of families in need. On top of that they are also identifying all of the units owned by the municipality that were distributed to users in a very un-transparent process and in many cases the beneficiaries are either city representatives or have family ties with them. The department of social welfare has also created a very inclusive supervising commission that has overseen the process for social housing distribution as well as they have extended the period for the housing contract to 3 years which is a very positive approach because it gives the beneficiaries a longer period to stabilize their economic well being. As for the makeup of the commission that oversees the distribution of the social housing in other cities, in all cases, the end decision rests with the city deputies that usually create ad hoc commissions that decide on the beneficiaries. In the majority of cases the cities also include certain representatives of the marginalized groups such as in the case of Gjakova with the Roma community representative, or with representatives of the HandiKos organization that advocates for the rights of people with disabilities, as well as women protection and war veteran groups.

In our survey with the beneficiaries of social housing the next issues were raised as the most problematic by the beneficiaries. Issues such as: water restrictions, sewage dysfunction, electricity restrictions, the misuse of the units, no maintenance of communal spaces, as well as bed construction and in particular no insulation, were identified as problematic by the units occupants.

The project team also conducted an on site survey analyzing almost all of the social housing stock in the partnering municipalities. The team analyzed the overall state of the social housing, the level of accessibility of the units, their proximity to build, technical and social infrastructure, etc.

The teams’ findings reaffirmed the problems identified by the beneficiaries such as the poor standards of the construction of the units; no thermal insulation; frequent sewage and water supply problems; no adequate lightning in the communal areas and in the immediate vicinity; no adequate maintenance of the communal spaces that according to the majority of the surveyed beneficiaries should be managed by the city authorities, etc. In almost all cases the sites lacked any kind of social, cultural or recreational services. The immediate vicinity in all cases associates more to an abandoned and forgotten space rather than one where there are people inhabiting it.

As for the accessibility aspects, the following stats are produced from the on site surveys with the disabled beneficiaries: From its total social housing stock in the city of Prishtina only 38 percent of it is accessible for the disabled users while 62 percent lacks any accessibility like ramps or elevators.

In the city of Gjakova the accessibility is merely 10 percent as is the case in Fushe Kosova. Ferizaj stands better than the latter with 26 percent, while the city of Gjilan has the highest percentage of accessibility with 69 percent. The accessibility percentage considered the immediate building accessibility as well as the sites’ vicinity. The above mentioned stats show there is a high need for representatives of physically disabled advocacy groups to be included in all aspects of social housing decision making and planning process.

Recommendations

The Legislature

Although there are positive shifts from the central government in moving forward on the issue of providing decent housing for its citizens by starting the work on the first Law on social housing. There are several issues that the central government should take into consideration during this important process. The words of Andres Iacobelli of Elemental Chile, best describe the way this issue should be understood: “Social and Affordable Housing should be understood as a social investment for the good of the society rather than as a social expense”.

The drafting of such an important Law for the overall well being of one nation should employ the highest standards of public transparency and inclusiveness. The same goes for the collaboration between the ministry and municipal departments for social welfare, whose work should be highly coordinated during this process. By Law the ministry is bound to call public hearings where they have to present the Law in front of the stakeholders and concerned citizens. The ministry did organize such a hearing, just once, and in that case failed or better say forgot to invite the public and in particular the representatives of Kosovo municipalities. The Ministry department of housing chose not to invite anyone by mail, or post the call on written or audio-visual media. They chose to publish the call for the hearing only on the Ministries newsfeed. Unfortunately due to this unprofessional conduct by the Ministry, the result was 6 people being present in the hall for the presentation of this important Law. Before anything else the Ministry should rethink the exclusive process on which they built this draft and reinitiate a new inclusive process that will be open and inviting to all interest groups.

The Law should be as comprehensive and detailed as possible, leaving no room for misinterpretation by local government, beneficiaries, developers or any other interest groups. As an example, our project team objected to the unclear statements in several articles such as Article 16, Act 1.3 that states that the municipalities should “provide land and accompanying infrastructure” or in the case of Article 20, Act 2 stating “the buildings should be built by adhering to the principles of environmental sustainability, energy saving and the use of alternative energy sources”. In both cases the interpretation is very broad and gives space to many interpretations.

Although we are proponents of housing for all, in the meantime we would propose that the Law should give a more flexible time for the beneficiaries to move to the stage of economic self reliance, thus by extending the period to which the beneficiaries could stay in the social housing units. For example if while residing in a social housing a member of the beneficiary family is employed and receives a median salary, the family should not lose the right to the housing after 6 or 12 months. This should at least be extended to 2 or 3 years. In that way the family would be given the opportunity to accumulate funds and move to the next stage of affordable housing.

During the meeting with the Housing Department officials we raised the issue of social integration of the beneficiaries. What if a given municipality constructs a social housing complex in the outskirts of the city, away from physical or social infrastructure? It is easy to conclude that for one Municipality to deem one project a successful one they would provide only the physical infrastructure. This is a case that is repeated throughout Kosovo when it comes to the construction of social housing. The same goes for the “principles of environmental sustainability” again its interpretation has no limits.

Stating in the Law that the housing should be “socially cohesive” does not do anything to stop future segregation of the most vulnerable from the rest of the population. Working models in Western Europe and Latin America that promote spatial (geographic) integration of the social and affordable housing beneficiaries already exist and should be presented in the local context.

The Law should also detail the creation of housing dedicated departments within the municipalities, which will coordinate their work with the Ministry of Spatial Planning and in particular the housing department.

Financing

After all the analyses done on site, interviews, surveys, law’s and case studies analyzed it is not so difficult to conclude that a holistic approach to the spatial or better say geographic integration of the housing stock and its beneficiaries, is the only way that one city or state can create inclusive and resilient societies, there is simply no alternatives to this conclusion. Kosovo has a great opportunity to rethink the way social and affordable housing is thought of and planned. As in the post WWII societies in Western Europe, Kosovo, as a society that is rebuilding itself and creating its identity should serve as a model to the region when it comes to providing social, affordable and decent housing to its citizens.

Although our chosen cities vary in population size, economy, built typology and so forth, they all have one thing in common. They all have an abundance of vacant housing units, and on the other hand developers that in large owe the Municipalities taxes or legalization money.

Let’s take the example of the Prishtina Municipality where based on the last conducted registry, there are around 15,000 abandoned housing units, and according to the local real estate agents in 2015 there were around 6000 to 8000 vacant units in prime urban neighborhoods. We’ll take the latter data as a reference number as it is more reliable when we speak of urbanized areas. Due to the fact that the units are recently built (in the last 5 years), in locations that has all the needed physical as well as social infrastructure, and let’s take into account the fact that if not all, the majority of the developers of these housing complexes throughout the city of Prishtina owe money in some form to the city, hypothetically speaking the Prishtina Municipality could easily distribute the 400 families that applied for social housing in 2016 proportionally considering the areas and even the buildings & neighborhoods economic make-up. Of course we are not proposing that all families in need be placed in a single typology in urban settings as we understand that there are farming families in need of housing accessible to land, thus all applications should be addressed individually. This is only possible while the construction legalization process is still undergoing. In future cases the city should employ this strategy to all new housing developments.

The proposed city housing department should base the creation of its housing stock on the spatial/geographic distribution strategy and create a working short and long-term implementation strategy.

This form of Public-Private partnership could be employed in all partnering Municipalities more or less. It is also true that some smaller municipalities do not have leverage of prime location vacant housing stock combined with developers debt as Prishtina does. In such cases the city should collaborate with the Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning as well as the Ministry of Social Welfare to subsidize the purchase of geographically distributed individual units from already existing and new housing developments.

There are other more creative ways to produce social and affordable housing stock without hurting the housing market or the developers to a certain extent. In many countries the pension fund is one that is used for the benefit of its own community and is invested locally, unfortunately the Kosovo Pension Fund chooses to invest its assets outside Kosovo.

A possible model, already existing in France, Netherlands and other EU countries, is the use of the funds financial surplus for social investment. In 2016 the total gain of the Pensions 1.5 billion euros fund was 18 percent, i.e more than 250 million euros. What if the cities would partner with the fund in creating a considerable social and affordable housing stock for their cities? A simple mathematical formula can logically explain the way this scheme could work. With the acquired money the city could build its spatially/geographically distributed housing stock by buying or giving tax incentives to the developers, or by jointly developing new housing units that would foresee the equal division of the created housing sold in market price, rentable affordable housing, and social housing. The Pension Fund itself won’t gain the immediate surplus that they do when investing in western banks and the stock market, but they will still benefit over a period of time from the rents on affordable housing, as well as they will drastically contribute to the social wellbeing of Kosovo society. On the other hand this model could drastically improve the quality of the construction sector. If the 3 way model would be employed the developers would have two thirds of their total cost covered by the city and the fund. In return the city would request that the developers employ the latest sustainability standards currently in force in Europe, and ask that the new developments adhere to the highest “LEED” or “Passive House” standards as well as provide the entire social infrastructure that is missing at the given neighborhood. The 3 way model would be beneficial to all 3 parties involved, the city would alleviate the needs for social and affordable housing; the fund i.e the state, would create better wellbeing for their citizens and have a steady return for their investment; as well as the beneficiaries of the social and affordable housing would benefit from the socio-economic mix of their living environment as well as from the guaranteed physical and social infrastructure that would be provided on site.

Our project team has produced a guideline with terms of reference for the partnering Municipalities in establishing advisory commissions for social housing which should feature representatives of marginalized groups so they may advocate for the needs of their communities as well as making the process as open as possible. We highly advise, not only the partnering municipalities but all others to adopt inclusive and transparent processes in social housing.